In general terms, when most people think about true investing, they think that they will be buying stocks and shares: the stock market.

In practice, though, most well-balanced portfolios will have other assets in them, such as bonds, but what is a bond?

First of all…what isn’t a “Bond” for our discussions?

We are quite specific about this term, but you will often hear the term used in a number of different ways:

- Building society bond – this is almost always a fixed-term cash deposit issued solely to a named saver.

- Investment Bond – this is usually a life insurance-based investment plan.

So, what is a bond?

Unlike stocks and shares, bonds don’t give you ownership rights in a company.

They represent a loan from the buyer (you) to the issuer of the bond (the company or government).

They have similar attributes to shares, in that:

- Generates income.

- There is a recognized market for them,

- Their value changes over time and market circumstances, but…

They differ in other ways and they have different jargon.

Bond Jargon buster

As with so many things, there are different terms for bonds than shares; here are a few:

Coupon: This is the interest rate paid by the bond. In most cases, it won’t change after the bond is issued.

Yield: This is a measure of interest (coupon) that takes into account the bond’s fluctuating changes in value. There are different ways to measure yield, but the simplest is the coupon of the bond divided by the current price on the open market.

Face value: This is the amount the bond is worth when it’s issued, also known as “par” value. Most bonds have a face value of $1,000 in the US and £1 in the UK.

Price: This is the amount the bond would currently cost on the secondary market. Several factors play into a bond’s current price, but one of the biggest is how favorable its coupon is compared with other similar bonds.

Duration: This is how long the bond is “in force” before the bond issuer gives you your money back.

Credit Ratings Agency: These are hugely active on the bond markets for bonds as they are for people.

There are a number of agencies, such as Standard & Poors, Moodys and each has their own scale to rate the quality of the bond.

Standard and Poors use the following: AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, B, and so on down to D.

Only AAA, AA and A are considered “investment grade” bonds.

Junk Bonds: the term used for BB and below for Bonds. These are usually bonds that are expected to struggle to make coupon payments.

To be able to attract your money, they will typically have to pay a much higher interest rate but are more likely to default.

Default: When a bond issuer pays too late, too little, not at all or goes bust.

Types of Bonds (by our meaning)

Corporate Bonds

These bonds are issued by companies, and their credit risk ranges over the whole spectrum. Interest from these bonds is taxable at both the federal and state levels. Because these bonds aren’t quite as safe as government bonds, their yields are generally higher.

High-yield bonds (“junk bonds”) are a type of corporate bond with low credit ratings

Government Bonds

These can be issued by any Government really, but we usually go for:

- American – known as US Treasuries.

- British – known as Gilts, as the original documents were literally gilt-edged.

How do you buy bonds?

There are mainly two ways:

- At outset from the lender.

- On the bond market, in the same way as you would a stock on the stock market.

In the UK, you can buy Gilts in two ways, as well. You can go directly to the Government’s Debt Management Office (DMO) when new stock is issued; or you can go to the market via a stockbroker or the Bank of England’s brokerage service, which allows stock to be bought and sold through any main Post Office.

Why buy Bonds?

- They have lower volatility.

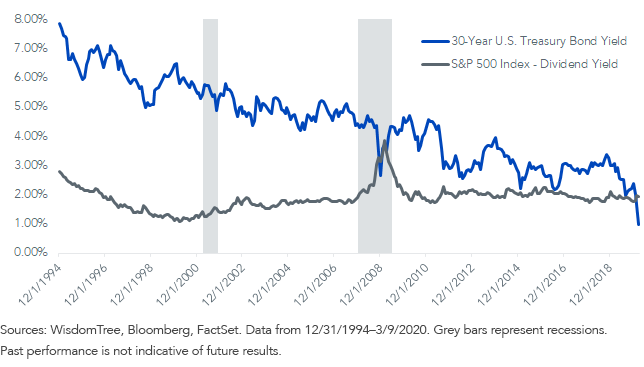

- Previously, they paid a higher coupon than a share (although hasn’t been the case for some time, really). As the following graph shows…

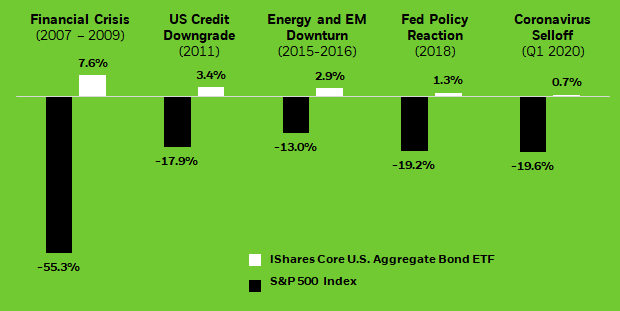

However, the main reason for buying bonds, being lower volatility meaning lower losses is still evident, as this chart shows:

Financial Crisis measured 10/10/07 – 3/9/09, US Credit Rating Downgrade measured 7/25/11 – 10/3/11, Energy and EM Downturn measured 7/21/15 – 2/11/16, Fed Policy Reaction measured 1/29/18 – 2/8/18. Coronavirus Selloff measured 2/12/20-3/13/20. (Apologies for the American date protocol)

In that case…why buy shares (equities)?

If Bonds still make money and don’t lose money like shares/equities, then should we avoid them?

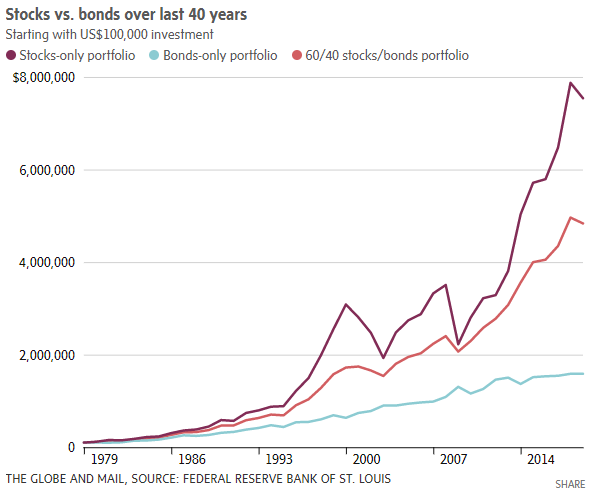

No…in the longer-term volatility is the driver of higher returns and so it is being embraced, not avoided, but having the balance is key.

Balance?

Effectively,

- Equities are engines

- Bonds are brakes

The more equity in a portfolio the faster it will rise AND fall.

The more bonds that you have in a portfolio the slower it will fall AND rise.

The following chart gives a feel for the effect of all bonds, all equities, and a mixture, which bears this out.

This is why we risk grade most of our portfolios in terms of equity content with zero % all the way up to 100% equity.

Most people tend to be between 40% and 60% equity, but this will alter how much risk you can take and over how long you can wait to recover losses.

Is it that simple?

The higher the bond content: the lower the volatility and risk, but…

Expect lower returns over the longer term.

Also, there are areas that you should be aware of:

- Lower interest rates push the price of a bond up, which means that you pay more than the face value. If you buy a bond with a face value of £1 for £1.50, then hold it to maturity then YOU WILL LOSE MONEY. This is known as capital erosion.

- If you are attracted to the higher rates of high yielding bonds, then you are being rewarded for taking higher risks, and bonds can become valueless, due to defaults and failures.

As ever, this is another area that we outsource to reputable managers to reduce capital erosion and defaults, to keep your money safer for the longer term.